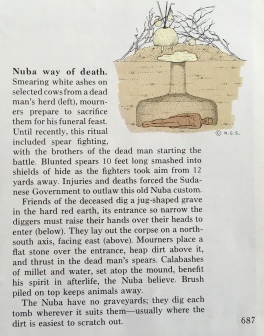

Manliness is but a Strong Heart – Nuba Mountains Proverb

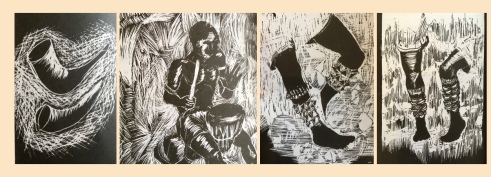

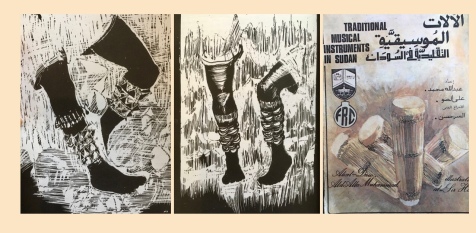

Traditional Musical Instruments in Sudan, University of Khartoum, 1985

Sky and Earth – A Nuba Mountains Folktale

“At the beginning of time, the sky and the earth lived together as one. The Nuba people remember a day when a young woman from the Nuba was grinding sorghum on the grindstone. As she worked, she unintentionally struck the sky with her elbow. The sky was insulted and decided to leave the place and take up residence far away from the earth. The people were unhappy about this and did not know how to continue their lives which had become gloomy and miserable without the sky, its rainy clouds and its shining sun. They held a meeting and agreed to send an envoy to the sky to persuade it to come back using the magic of his soul.

The envoy went and no-one knows what happened in the sky or how he convinced the sky to come back. It agreed on one condition: that it would return only once a year and would be invited to return each time. This is how the seasons were created and how the Nuba Mountains received their first Kujur, the rainmaker, who since that time has continued to mediate between the earth and sky. The kujur has passed on his ability to make rain to his children and the children of his children. The same traditional grindstone, the murhaka, is still used to this day in the plains and mountains.”

“Shaven and dressed with the help of his community, the kujur is adorned with powdered river mussel shells and his insignia of power; amulets and ceremonial spears….. A mediator between the divine, spirits and humans…” Solemn rites to secure the autumn harvest.

Read more in this colonial account How a Nuba Chief Becomes a Kujur

Sand in My Eyes, Enikö Nagy, p 384 and p 458

This blogpost is dedicated to Dave Flower RIP, a remarkable teacher and friend who understood that sometimes the road must be walked barefoot.

The post draws on the work of a British medical officer stationed in the Nuba Mountains under 1930’s colonial rule. It should not be understood as a justification of British colonialism in any way. In coming posts I look forward to interviewing Nuba friends on Nuba women’s dances still celebrated in The Nuba Mountains today.

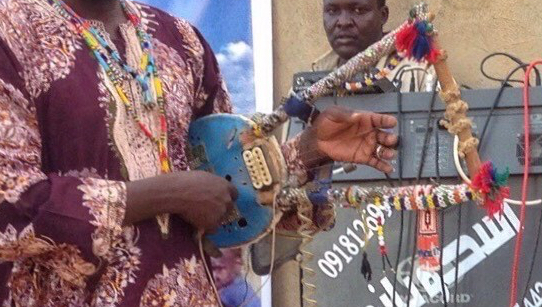

The kirang, used by the Nuba of Southern Kordofan to accompany the kirang dance -Traditional Musical Instruments in Sudan, University of Khartoum, 1985

Readers are welcome to reproduce any photos in this post taken during Nuba cultural celebrations in Khartoum 2015-17

Kambala Scenes Kambala and the Colonial Gaze Harvest and Whip

Kambala Scenes

Kambala dancing in Khartoum Province in 2015-17.

The Kambala festival celebrates the safe harvesting of grain and is associated with initiation rites for young Nuba men. The Kambala dance is performed to mark celebrations throughout the year. Kambala and Nuba wrestling have become emblematic shorthand for Nuba identity.

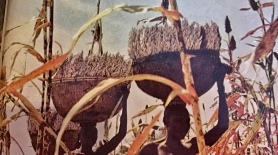

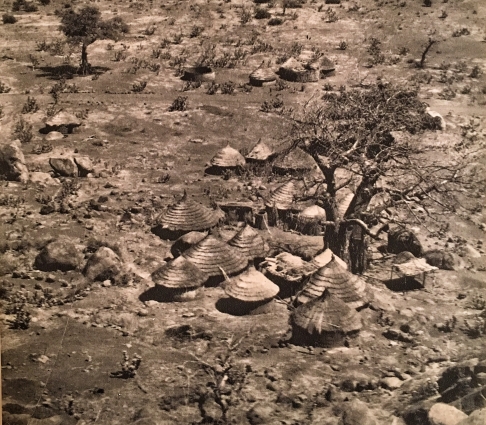

Grain harvesting – National Geographic, Vol. 130, no.5

“In Arabic the (Kambala) festival is also referred to as the Sibr El Esh or more specifically the Sibr El Nagad, The Festival of the Early Millet. It is held once a year, generally starting some time in September, in the season called the Darat in which the rains are closing, and when the nagad, the early quick-maturing millet, has ripened and is fit for consumption. it lasts twenty-eight days, a complete lunar cycle…..”

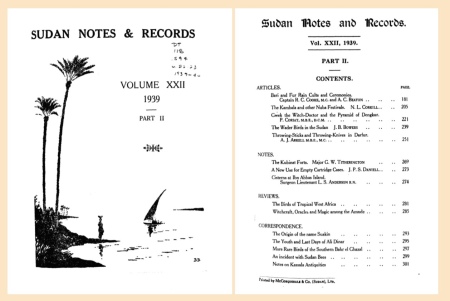

The Kambala and other Seasonal Festivals, by N.L.Corkill, Sudan Notes and Records, pp205-220, Vol. XXII, 1939

Kambala dancing in Southern Kordofan in 1988

![]()

Kashkoash rattles, known as madendi in Nuba, are “made by putting small stones or hard seeds into a container such as gourd, calabash, empty cans or locally made tin balls” –

Traditional Musical Instruments in Sudan , University of Khartoum, 1985.

Colonial accounts describe young men between the ages of 8 and 35 charged with making kashkoash immediately after “the fall of the whip” (see below) heralding the start of the Kambala festival, and using dom or doleib palm leaves containing small, preferably white, stones. (Corkill)

Enjoy them in action here:

![]()

“The favorite instrument, played by young men for musical accompaniment, is the five-stringed lyre. It is played everywhere: “herding cattle, walking around, sitting under a tree. It has different names, including fedefede, (Tumtum Nuba), benebene or beriberi (Masakin) and kazandik (Miri). The resonator consists of a piece of cowskin-covered calabash.”

The Garland Encyclopedia of World Music – Africa

Kambala and the Colonial Gaze – Harvest and The Whip

Kambala and the Colonial Gaze – Harvest

Extracts below taken from The Kambala and other Seasonal Festivals, by N.L.Corkill, Sudan Notes and Records, pp205-220, Vol. XXII, 1939

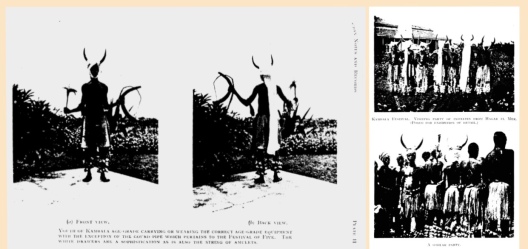

“They progress in file in a circle, stamping their leg in rhythm so that the rattles sound in unison. They do not sing but rather roar and low like cattle and from time to time clash their horns against those of a fellow celebrate.” (Corkill)

“They bind bull’s horns on their head with head-cloths and dance. The girls watch only. Men have rattles on their legs and the hair of rams in armlets above the elbows.” Initiation ceremony of Nuba youths recounted to Corkill in 1934. The bull horns, called Ido ma Kamala in Nuba, represent strength and are kept safe for use in successive years. (Corkill)

“In the language of the of the Kadugli Nubas, the word Kambala apparently denotes an age grade of some 12 years, from about 10 to 25. The youths composing the Kambala age-grade and initiates to it are ceremonially beaten, the millet is ceremonially involved and the age-grade wear horns of bulls or cows or both. Every youth must dance and be whipped yearly for six years. If he eats new grain before being whipped, when next whipped the whip will not fall on his back as intended but will curl round and blind him in one eye.”

The Kambala and other Seasonal Festivals, by N.L.Corkill, Sudan Notes and Records, pp205-220, Vol. XXII, 1939

“In 1935 a party from Damba came into the the writer’s garden lowing like cattle, ringing bells, called kilendi in Nuba, and dancing. Their accompanying elders explained that this was for the millet.”

Writing for Sudan Notes and Records in 1939, Norman Lace Corkill, a young British Medical Officer stationed in Kadugli, was quick to acknowledge that his paper on The Kambala and Other Seasonal Festivals of the Kadugli and Miri Nuba was the fruit of an “accidental composite and not a deliberate study”, admitting “there must still be many interesting details unrevealed.”

Seventy years on, Corkill’s honesty and British understatement still shine through his carefully observed and often warm accounts of Nuba Mountains life under colonial rule even though we are acutely aware now that his narratives are both informed and deformed by the imperialist gaze of his times.

” The women of the community are disposed round (the men) in an outer circle. They so not sing or clap and they are not dressed in any particular way but holding cow tails mounted to sticks in their hands, called tumoi in Nuba.. They dance by moving their feet and bodies in rhythm but do not move their position.” (Corkill)

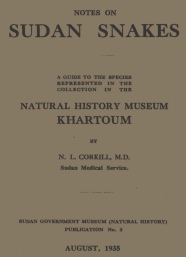

Norman Corkill would go on to have a distinguished medical career in the Middle East and was to write papers for Sudan Notes and Records and the Lancet on topics as varied as Sudanese venomous snakes, the effects of Kordofan climate on meningitis outbreaks there, the impact of locust plagues on child nutrition in Sudan and smallpox epidemics in Jeddah. There is a brief Lancet biography at the end of this post.

Read his short article on A Kadugli Cobra Trap – N.L. Corkill

While he believed rites of passage such as the Kambala and its sister festivals of the antelope, rain and fire would inevitably be reshaped through Islamic influences or fade away over time, Corkill recognized the sheer power of agriculture “to generate practices “as tenacious of life as any.” And the Nuba informants of his day powerfully echo this realization in their comments to him:

“Harvesting before the Kambala is taboo”

Kambala “is for the grain and for the children”

“If the festival is not held, there will be no luck, grain will fail, children will die and cattle will not multiply”

“There is to be a big Kambala because so many people died in the recent (meningitis) epidemic”

Threshing and winnowing sorghum and millet in the Nuba Mountains today

Failure of kujurs (Nuba spiritual leaders) to secure a good harvest could expose them to more than just criticism. In 1937, Corkill recalls, and I imagine, with a wry smile –

“The local kujur, Lord of the Millet and the Rain, was beaten because the millet beer was small in quantity – meaning the season’s grain was poor. A bystander gratuitously informative said ‘we beat him also if the rains are poor.'”

The Kambala and other Seasonal Festivals,

Gawain Bell, writing just a year before for SNR on Nuba Agricultura Methods and Beliefs also recounts the sowing and harvesting ceremonies so central to Nuba life and described how communities negotiated seasonal challenges such as severe winds and droughts through hard work, ritual interventions and community cooperative undertakings, known as nafir. More importantly, perhaps, Bell was writing at a time of “fundamental changes” in Nuba life brought about by colonial introduction of money crops such as cotton and tobacco. “It was the custom formerly for every young man to assist his parents in cultivating until such time as he married”, he explains. With the advent of money crops “the communal method is tending to change to one more individual” and young men, though still using the nafir system for food crops “prefer to run an independent allotment where a money crop is concerned”.

Nuba village and baobab tree, 1930, Der Dunkle Erdteil, Atlantis Verlag Berlin

Scroll down to read Bell’s accounts of “saluting the grain” and harvest thanks-giving rituals.

“The Nuba are earnest and industrious farmers and there is no period of the year in which they are not engaged on some stage of their livelihood” – G.Bell in 1938

Grilling early harvested sorghum, photo from Sorghum, Sudan’s Staple Food of All Times Learn more about the celebrations associated with the harvesting of sorghum and millet in the Nuba Mountains and elsewhere in Sudan in the Sudanow article above.

“Youths of Kambala age-grade carrying or wearing the correct age-grade equipment with the exception of the gourd pipe which pertains to the Festival of Fire.” Kambala and Other Seasonal Festivals of the Kadugli and Miri Nuba N.l.Corkill, Sudan Notes and Records, p205-220, Vol. XXII, 1939

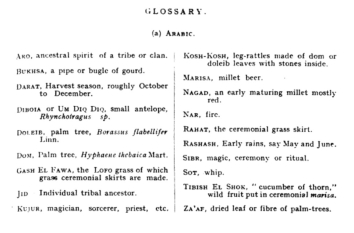

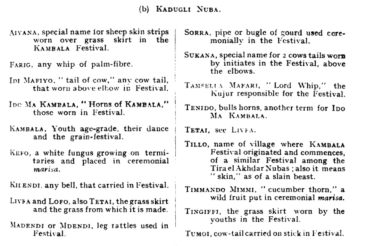

Corkill’s glossary of Kambala terms

Corkill’s glossary of Kambala terms

Corkill’s glossary of terms

Kambala and the Colonial Gaze – The Whip

Harm and lashes are for men, not women/ Today, I will be whipped on my back / I will bear the lashes / Even if they are the stabs of stars / I will be lashed / So let all people hear this / And speak forever more of this day

Quoted in Sand in My Eyes, p 183, from a Kambala song from the Nuba Mountains, translated from a Nuba language by Mohammed Harun Kafi, in Kafi (2010) p. 84

Inside the Kujur’s sacred home. It is entered barefoot only and exited by walking backwards. Upon a kujur’s death, his home is destroyed and a new kujur’s dwelling erected on its remains. Information and photo from Sand in my Eyes, Enikö Nagy

“Initiates live in the hut of the kujur for the whole twenty-eight days of the festival and are beaten at least once every day for the first three days .” (Corkill)

Corkill’s Account of the Whipping Ceremony

“In September, the Kujur who is the Lord of the Festival (Sid el Sibr) in Tillo makes a whip of plaited dom palm fibre. This whip which is called in Nuba farig, he places inside his hut in the thatch above the door, together with a head of the early maturing millet called nagad, a fruit of the plant called in Arabic Tibish el Shok or cucumber of prickles, and in Nuba, timmando nimmi, and the skin of a slaughtered she-goat. The old whip, which has been replaced, is taken by the kujur in company with three or four old men and thrown in to running water…. The falling of the whip is the signal for the ceremony to commence.”

“When the grain is ripe the whip will fall. Should it fall too early, it may be replaced. The festival lasts in Tillo twenty-eight days from its fall. The whip falls, the Kujur seizes it and cried out in a loud voice.”

“After the whip has fallen, much marisa (millet beer) was drunk”

The grass skirts are known as rahat in Arabic and Corkill noted four Nuba terms for them; tetai, tingiffi, livfa and lofo – “the latter also being the name for the grass from which it is made.

About eight or nine days into the festival Corkill recounts –

“About ten youths aged say twelve to sixteen were dancing in a ring …………They all bore whip-marks but none were being beaten at the time – about two in the afternoon. Two smaller boys aged about ten who were standing in the ring of onlookers were pointed out to the writer as initiation candidates. They were not dressed up. Their backs each bore the wounds of perhaps a dozen lashes, and they seemed very proud of them……..In the centre of the dancing ring of youths were one or two dancing women carrying branches of the evergreen tree called in Arabic Habila.

They were pointed out as mothers of the candidates for initiation ……..The local kujur who is lord of the Kambala, of the Millet and of the Rain, now suddenly appeared. He was dressed in an old military great coat, but over this at the back he had fastened the skin of a cow. Whether this was for protection from the whips or was of ritual importance was not clear. There was now a great deal of uproar, rushing about and merriment. One of the elders hit the kujur a violent crack on the back with the whip and the other elders with their whips violently flogged the ground around him. They explained to the writer “we are hitting him because the marisa is too little”……..Another bystander said ‘we beat him also if the rains are poor’. The kujur himself seemed quite happy about it…..”

“About thirty yards away is a ring of about forty elders each with a palm fibre whip like that of the kujur. They beat on the back any youth who chooses to dance round the inside of the ring. All youths however do this voluntarily because ‘their fathers did not allow them to refuse and also if they did refuse the girls would laugh at them'”

![]()

Full Circle – The end of the Festival after 28 Days

“At about four or five in the evening, they remove their grass skirts, goatskin strips and leg rattles and take them in their hands together with their whips. The kujur goes in front and leads them with a branch of a thorny tree called in Arabic nabag, in his hand, to an ant colony. All have the festival equipment in one hand and a rock in the other. They place their equipment on the nabag and the rocks on top of them. They are left to disintegrate by natural causes.” (Corkill)

Nuba tribesmen wearing chainmail colonial authors were told to be of medieval origin. Plates from The Vast Sudan, 1924, by Major A. Radclyffe Dugmore, p 108 and p 114

Norman Lace Corkill – The Lancet Biographical Summary

G.Bell’s accounts mentioned above

More colonial accounts from Sudan Notes and Records

Nuba Initiation Ceremony The Sibrs of the Tail and the Shield

Notes on the History, Religion and Customs of the Nuba

National Geographic, Vol.130, No.5, November 1966

George Rodger Sudan Kordofan photography The Nubas 1949