The Drowning by Hammour Ziada

A Review in Wartime

“In front of Radiya’s amazed glances, the old woman’s trembling hand moved the razor along Sukaina’s cheek. The blood flowed and the woman closed her eyes, silently biting her lips. Izz al-Qawn dressed the wounds with a piece of linen dipped in cumin and coffee beans. Sukaina opened her eyes, blood covered her face. Linen and coffee grounds oozed from her wounds. She looked at Radiya, and said in a tearful voice, “Are you happy with this, O best of women?”

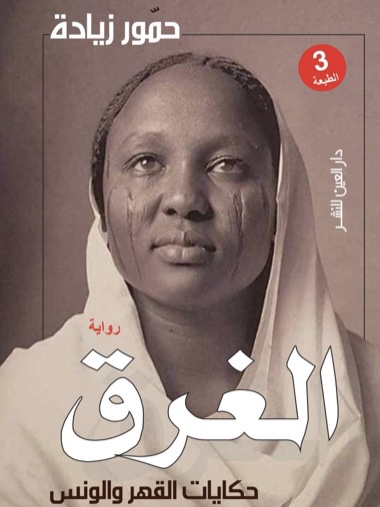

From The Drowning, Al-Gharaq, original Arabic edition cover above, published late 2018. The cover shows a young northern Sudanese woman bearing the traditional facial scars, or ash-shuluuh prevalent among Sudanese tribes until the late 1990s. Sukaina is one of several compelling women who shape the novel’s course, embodying both grace and chilling cruelty.

Above, colonial-era G.N. Morhig postcard showing northern Sudanese women welcoming the rise of The Nile.

“The paradise river carried wooden boats, conquerors’ barges, the corpses of the drowned, and the victims of massacres. Married couples, children after circumcision, and women after childbirth plunged into it….The paradise river often dried up and destroyed. But every time it went back to what it had been: a gentle river, coming from paradise.”

The Drowning

The Nile, Northern Province, photo CC Dreamstime, used under licence. For more on the folklore and cultural impact of the Nile, see:

The Night They Held the Angry Nile at Bay

The Drowning by Hammour Ziada

“In Khartoum, be afraid of just three things; God, electricity and the military. Here we are safe for a while. We fear God, the flood, and worms in the dates.”

When a woman’s corpse is washed up on the banks of the Nile in the village backwater of Hajar Narti, a palm-groved dot on the river’s bend somewhere between al-Gharba and Dongola, Fatima renews her mute vigil by the waterside. “Twenty-eight years. People had died and had been born. Palm trees had been planted and uprooted. The flood had destroyed gardens and people had planted others. But Fatima never despaired. Twenty-eight years.” The year Hajj Bashir married Sukaina bint Badri – 1941, Fatima had come to search for Su’ad, her missing daughter.

Hammour Ziada, award-winning writer and journalist, sets his novel in the still newly independent Sudan of 1969. With its tonal echoes of Tayib Salih’s Wedding of Zein, the author immerses us in the world of Hajar Narti as the political turbulence at the centre of power, Khartoum, with its revolutions, coups and counter coups, radiates outwards, touching the lives of its inhabitants.

Threading brightly through its village tales, its folk and feudal lore, are the life stories of the novel’s men and women protagonists as they navigate a changing Sudan. The Drowning is spare and disarming in its telling of love, grief, the dashing of dreams, the jolt of casual violence and the quiet agency of the dispossessed in a time when debts of family honour had always to be paid, when daughters were graduating from medical school for the first time and former slaves could still be denied an education on a whim.

How Hammour Ziada’s characters will bear the weight of convention, of social and family codes informs the dramatic tension of the novel. Will they do so with equanimity, or be consumed by it? The author is perhaps at his most compelling – and most compassionate – in his portrayal of the former slaves of the village for whom the abolition of slavery has meant merely the substitution of the term “uncle” for “master” .

The Arabic edition of the novel bears the subtitle I roughly translate as “Tales of Oppression and Time Spent in Good Company”. And for anyone who has lived northern Sudanese village life in the latter part of the last century, the novel vividly evokes that good company with tales – often witty and transgressive – told by villagers between bouts of snuff taking and heavy drinking. The political battles of colonial times are relived, feuds nursed and reputations deliciously and permanently dented by the humble scorpion.

The drowned dead come to rest on the Nile’s banks at Hajar Narti. For some of the living, only by fleeing Hajar Narti can they escape drowning.

The novel bears a message of hope as longed for happiness is found, and a prescient warning. “They are a flood, Bashir, a flood that will sweep away everything. We will drown. The whole country will drown” Bashir’s elder brother reminds him, as they consider the tide of events consuming the capital.

Photos above, Northern Province Nile villages, 1980s. Inset above, a painting seen on the wall of a ad-Debba restaurant, same period.

“Dawn never caught her sleeping. She would sit in the darkness before dawn, get her things ready, sterilize her cups, mix her cloves and cardamom and ginger, boil the coffee beans, then crush them in a wooden mortar until they became soft.”

Fayit Niddu, former slave and mother to the young, untamed Abir, begins her day in The Drowning.

More on Hammour Ziada: